Perhaps it’s not as odd as I think.

A short while ago, holding an X100V in my hands, I was scrolling through the shooting menu for in-camera film simulations. There were choices for Provia, Velvia, Astia, Eterna, Acros and more. I smiled at each option, remembering the days when I would place a canister in my camera, stretch the film across the back and insert the tab into the spindle.

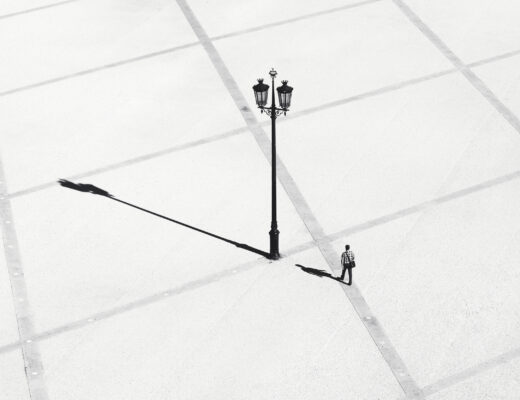

Featured image above / © Pete Duval.

The click of the closing back always sounded like the beginning of something important.

The world has gone decidedly digital. But nearly every college photography program teaches darkroom methods and skills. Why? It’s not just a history lesson.

No one in the enthusiast market is making SLR cameras anymore and a 35mm film camera in working order is becoming rare. But film has not gone away. Perhaps, I thought, it’s a bit like vinyl records. Yes, nostalgia is a strong motivation for preservation for those of us old enough to have heard vinyl first. Vinyl simply sounds different than digital sound. Better or worse is a matter of taste. But it’s a difference of kind and not just degree.

I remember, in surprising detail, developing b&w film in my high school darkroom. I remember the HC-110, the stop bath, the huge enlarger, the rolls of negatives hanging from cords strung across the room. The process itself was romantic and alchemical.

What is it about film, I wondered? What are we holding onto, and why?

I reached out to Manny Almeida, President of the Imaging Division at FUJIFILM North America Corporation, for insight.

“The photographic market peaked in the United States around 2003,” he told me. “That was the peak year for film sales. Depending on whose research you look at, there were roughly 860,000,000 rolls of film sold that year. Since then the market has declined and today it’s roughly 2% of what it used to be. A little bit less than 2%.”

“But to say that it’s just a market is too broad because there are segments. There is a professional segment, there’s a black and white segment, there’s a color negative segment, and there’s a QuickSnap—one time use camera—segment. And they are all somewhat distinct.”

Is the film I put in my camera today the same as what I used 20 years ago, I asked?

“There’s really very little difference between film today compared to 20 years ago. If there are differences, it would be in products like Neopan Acros II, 100 ISO. That is a new product. And some of these changes have been necessitated because of raw material availability. Some of the materials are either no longer available or no longer acceptable by today’s environmental standards. The acetate is basically the same. The changes have been primarily in the components that make up the chemicals.”

“But the real beauty,” he said, “is that consumers aren’t using it and thinking “oh, this is from 20 years ago.” They’re using it for a purpose.”

Fujifilm sent me four rolls of film, two color and two black and white, to check it out. I decided to spread the rolls among friends I knew were still into film and producing interesting work.

I gave a roll of Neopan Acros II to Andrew Hendricks. “I’ve been curious to shoot Fujifilm Acros for some time,” he said. “When I first started shooting film, I always heard it was a beautiful film to work with. That curiosity grew even more when Fujifilm decided to reintroduce the film as Acros II.”

“I wanted to shoot Acros II at box speed,” he continued, “but 100 ISO is a bit unusual for me (especially monochrome in the middle of winter). I tend to shoot black and white in mixed lighting conditions and hardly ever in ideal light. Something at 400 that I have confidence pushing to 800 or 1600 ISO is my jam. Being slightly stubborn, it was hard for me to break my habits and seek out the kind of lighting I really wanted to see on Acros II. I had to embrace the winter photo walk. I committed to going out on a few cold December days to capture the neighborhood around me. I’m really glad I did. Not only was I very pleased with my roll (it’s sharp, great contrast, and the grain isn’t obtrusive), I enjoyed the little push out of my comfort zone. I found a few new areas that I will definitely revisit, and a little shake-up to a creative routine is always beneficial; no matter how reluctant I usually am. That’s why I started shooting film in the first place. It’s surprising how such an old medium can continue to keep me on my toes and push me to something new.”

Is there still research being done to advance film technology at the consumer level? I asked Manny.

“Film is basically organic chemistry. Digital is basically electronic engineering. We still have a fair amount of organic chemistry research that goes on, but it’s primarily because of our instant film product, not our traditional 35mm or 120 products. Why don’t we do a whole lot of research? Because it was worthwhile when we were selling billions of rolls of film. Today the market is so small it doesn’t make sense. But really, by 2000 film had been so fine tuned by every manufacturer, it was so good, our quest for fine grain, for brighter colors, for color accuracy and fidelity, basically reached a zenith. And when you look at color negative film, it is not the sole reason a print looks the way it does. FUJIFILM has continued organic chemistry research in color paper. And in fact, we’ve introduced a number of different color papers. We’ve optimized color paper for digital printing. Our latest introduction was only a couple years ago. So we continue to do research on the paper side, which can have a huge impact on the final look and feel of the print.”

I gave a roll of Fujicolor 200 film to Pete Duval.

“The color immediately brought me back to my days shooting film,” he told me. “Back then my favorite was Velvia, which I shot on an old Rolleicord. That film seems like a different visual genre than this one, which, though not as over-the-top gorgeous as chrome, has its own quiet joys. After the expediency of digital, shooting film feels a little like dressing in period costume. Or writing with an electric typewriter. And yet, that we’ve lost something in the transition from analogue should be obvious. Among these things is the sense of corporeal seriousness that accompanies working with film. The stakes seem lower with digital. That said, it’s hard not to argue that digital has allowed us to soar. But working with analogue seems somehow more “moral,” in the sense that the analogue has very real consequences in the world that only register as a quaint dream to digital (which is why we have the nostalgia of “filter porn,” of apps like Hipstamatic, which I love, by the way). If you’ll allow me a theological metaphor, working with analogue makes of one an Incarnationalist, because the medium exists in the same tangible “fallen” world as the image, which cannot help but inform the image in more honest and, that word again, moral ways. It makes sense to speak of the “thisness”—the “inscape” as Gerard Manley Hopkins calls it—of the film image, but that idea makes no sense within the ethos of digital imagery. I should practice what I preach. I rarely shoot film anymore, but I do love Fujifilm’s amazing digital film simulations, and I own an X-Pro3.”

“Daido Moriyama says somewhere that he ‘can’t photograph anything without a city.’” Pete continues. “He has Shinjuku in Tokyo. I have Jersey City, New Jersey, a gritty urban enclave directly across the Hudson from Manhattan. As a photographer, I can’t get enough of the texture and the light, which in and of themselves are almost enough to live on, but also of the constant presence of time made visible, in decay and accumulation. I love to rise early when the light is long and seems to ennoble every mean thing it touches. You have to walk a city many times to see it. It helps to do so with different cameras, different lenses, which work to shift the “phase” of your seeing. Different times of day, of course, and different angles of attack. Shooting film effects this phased seeing, too. I’m not sure exactly what I’m looking for, but I’ve always thought of individual photographs as poems rather than stories. I’m not consciously assembling a set or collection of photographs; I’m looking for something complete in itself, self-contained but endlessly and mysteriously referential, like a poem.

Why are film simulations so appealing in digital cameras? I asked Manny. I’m old enough to remember shooting with film, but many younger photographers have no real memory of film.

“A lot of consumers do remember film,” Manny said. “A lot of consumers, of course, don’t. Most millennials know that film exists. But most Gen-Zs are coming into it saying what the heck’s film? But the main reason our digital cameras have these features is we were a film company. We understood the nuances of Velvia compared to Eterna, compared to Provia, and then compared to color negative film. We felt that it was a great way to differentiate our cameras and all of a sudden found ourselves with a great deal of following for our film simulation in the cameras. And it really does make a difference. I shoot with an XT-2 and I use film simulation all the time because it kind of takes me back to what I knew.”

Of course, film has its challenges. I gave a roll of Fujicolor 200 to Vinny Reusch. “I shot exclusively with a 50mm 1.4 lens,” he said. “I was excited to shoot a roll of film again. It’s been a few years. My first adjustment in moving from digital was remembering to advance the film. After half a dozen shots, muscle memory kicked in, and this became second nature. I enjoyed returning to an optical viewfinder after nearly a decade with an EVF. I felt more immersed in the scene, and, despite the fact that my OLED EVF probably gives a highly accurate preview, I felt that I could better anticipate the look of the photo when using the SLR. Manual focus, like advancing the film, quickly became second nature, and slowed me down less than I’d thought it would. I may have missed focus occasionally, but my digital often focuses on the wrong thing, too. What I could not get used to, however, and don’t ever want to go back to, is a fixed ISO. Two-hundred-ISO hampered me in most of my photography, enough so to dampen much of the nostalgia I had for film. Inside, the lack of light was a problem, outside in the snow, too much light controlled my depth of field options. Yes, I could screw on neutral density filters, but do I want to? Turns out I don’t. I’m spoiled. Fixed ISO has become a deal breaker for me.

Shooting now with a Fujifilm digital camera, I have a camera that gives me much of what I missed about film in the early days of DSLRs with their bloated, bulbous bodies, PSAM controls, and fiddly plastic dials. My Fujifilm looks like a “real” camera should. My shutter speed and aperture controls where they’re “supposed” to be. Although focus peaking is ugly rather than elegant in comparison to that beautiful split-image encircled by the micro-prism ring, it gets the job done when I want to shoot with a legacy lens. In short, my trip down memory lane proved to me that you can’t, or perhaps shouldn’t try to, go home again.

“What’s interesting for us, and it’s pretty exciting,” Manny said, “is in our evolution creating digital film simulation, we used some of the original film engineers that had a large part in creating the counterparts. And all of a sudden they are joined with digital imaging, creating these simulations and running the tests. But we didn’t create it to really emulate film, per se. We don’t emulate the grain, for example. We created it so it would emulate a look and feel.”

“Way back we created a product called Reala film. It was our first film with a fourth layer. Typically films are coated with sometimes up to 14 layers, but they have three intrinsic layers of color. Cyan, magenta and yellow. Reala had a fourth layer. And what Reala was able to do was see much more like the human eye. You know, if you walk from a room that has incandescent light and walk into a kitchen that has very bright florescent lights, people don’t look yellow in one room and green in another room. Our optics compensate. Our brain compensates. Film can’t do that. If you take a picture under incandescent lighting everything’s yellow and orange. If you take a picture under florescent lights everything’s green. And they both look terrible, though the incandescent is more pleasing. Reala was an attempt to emulate the way the human eye sees. So, films go well beyond just having grain and having contrast. There are a lot of other characteristics. We tried to build some of those characteristics into the film simulations in the digital cameras.”

Given the current re-popularity of things like vinyl records, I asked, and retro-stuff in general, is there going to be another wave of film? Is it going to come back?

“I don’t think it’s going to ‘come back,’” Manny said. “But it’s holding pretty steady at the moment, and it’s held pretty steady for the last few years. What’s interesting is that you have to break it down by application. QuickSnap, for example. Traditionally, you’re sending your kids to camp or you’re going to the beach and you don’t want to chance harming your camera or your cell phone. You don’t want to get it all muddy or wet or drop it on a rock and see it break. So you send off a QuickSnap or multiple QuickSnaps. That market has remained the same. What’s been added to that market is that it’s increasingly difficult to find decent, used, 35mm cameras. It’s real easy for someone who says they want to try film to try QuickSnap. The results are not going to be the same as a good quality 35mm SLR. But at least you get the feel and the look of film.”

I gave a roll of Neopan Acros II to Jon Solinger.

“This assignment came at the right time for me,” he said. “After some 15 years since leaving the darkroom for digital tools, I’m teaching a film-based photography course this semester, giving me access to processing and printing facilities.

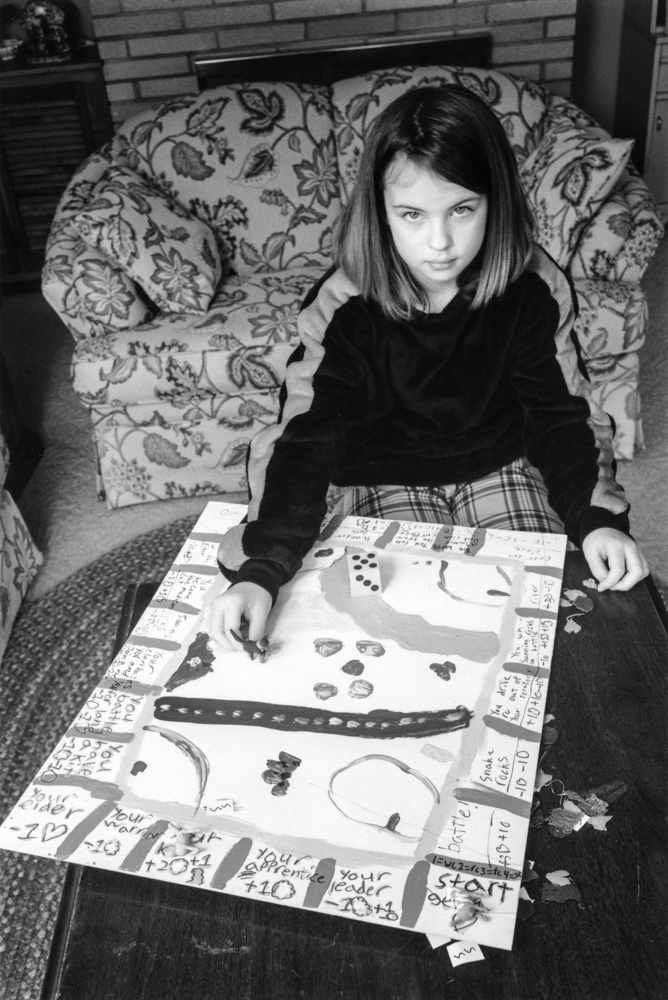

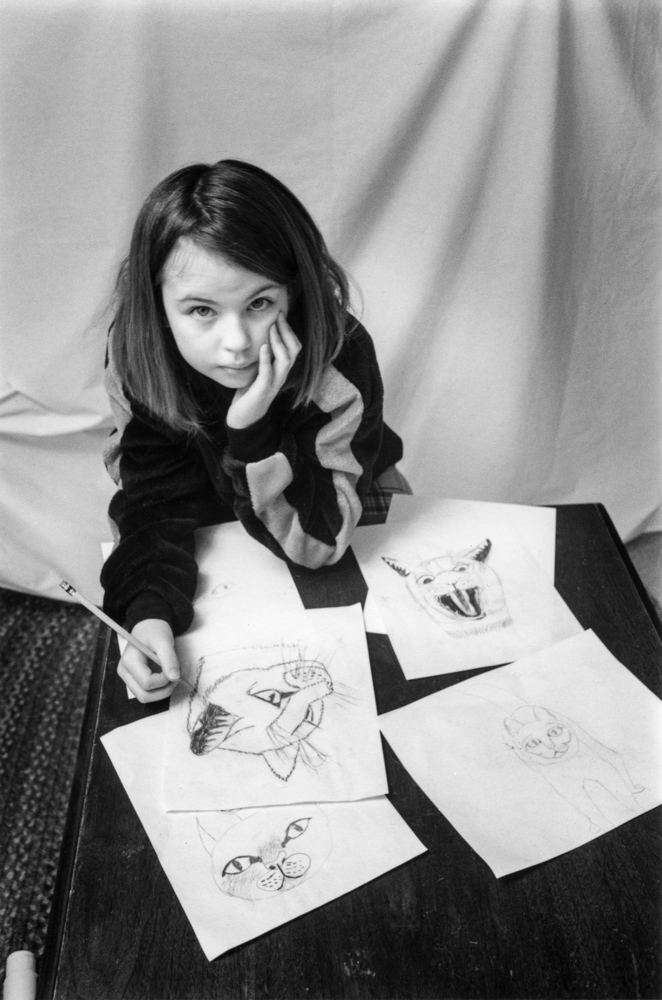

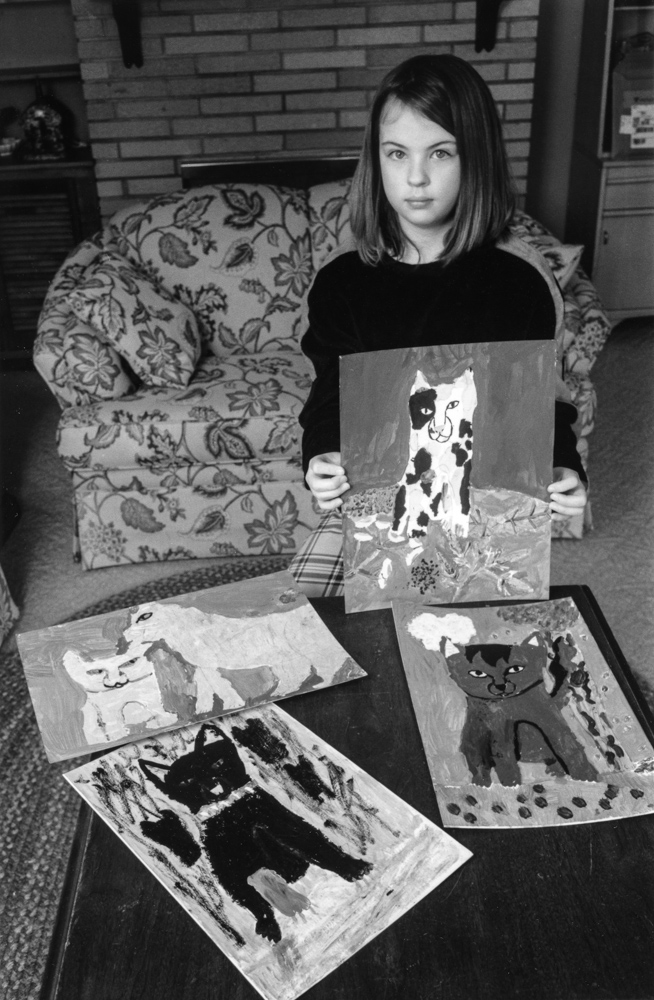

“I photographed my fifth-grade daughter Violet with her paintings, drawings and a board game based on characters and stories from her favorite book series, using Acros 100 black and white film,” Jon continued. “I enjoy photographing people in places and with objects related to their work-life that give clues to the subject’s personality. Play is the work of children. Violet’s serious and dignified expression in these portraits shows her pride in these products of labor, heart and mind.”

“Photography is all about light,” Jon said, “in both technical and aesthetic terms. Photographing with film brought my attention back to the light; is the subject lit right to get a printable negative, how am I using light to control the visual form of the image? I checked the meter reading and camera settings again, too late after the film is exposed. Printing in the darkroom: I witness again the action of light and chemistry on physical materials. I manipulate light with my own hand, dodging and burning-in, making tedious test prints, watching the clock to time the process steps. Finally hitting the mark, I see: this gelatin silver print really is an object of a different kind than images on a screen or even digital prints on paper. Using film, I worked with the light in a more conscious and physical way from beginning to end.

“A lot of professionals are using film because digital photography has enabled two things,” Manny says. “It’s enabled you to not have to worry about an ISO. As the light goes down you change it. And the other thing it’s done is create spray-and-pray. Now I can take 10,000 pictures and one of them is bound to be pretty good. I think digital has actually created laziness in some ways in the professional community. But professional photographers who are shooting film, they’re slowing back down to that old speed. They’re realizing they’ve got 36 exposures and if they’re using 120 film they might only have eight or 12. So you really have to think through composition and focus and lighting. It gives them this slow down method. They may not be using film because it creates far better quality and higher resolution. They’re using it because it creates this reality in the final image that they can deliver to consumers. If I’m shooting film and everyone else is shooting digital, my images are going to look different and you’re going to say wow, this is really authentic. This looks real.”

Do you think every photographer should begin, should cut their teeth on film? I ask.

“I think it would force them to be better photographers. It would force them to shoot less. It frees up the photographer’s time to be an artist.”