The shot below is probably the most important Fujifilm image I have shot in the past 4 years.

I am joking obviously, at least with regards to the contents of the image. This is by all accounts a crappy, ill-composed flash-lit picture of a toy bulldozer.

Yet, it’s the fact that it was obviously lit by flash that makes this picture so interesting. Because… look at the Exif-info: that 1/8.000th isn’t a typo. No, after 5 years of Fujifilm X-series, it marks the start of a new era where Fujifilm users who like flash photography, will no longer be limited by their Fuji’s sync speed. On an X-Pro 2, that is 1/250th, on an X-T1, it’s 1/180th of a second. From now on, you’ll be able to shoot with flash at up to 1/8.000 of a second. The little wonder of technology that makes this possible is a radio transceiver called the Cactus V6 Mark II. And the opening shot is the first image I shot with it.

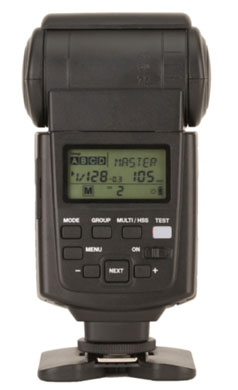

As I wrote in this review, I was already quite fond of the original Cactus V6 Mark I as a radio trigger for Fujifilm cameras because it lets you control the power of say a Nikon SB900 manually and remotely by connecting it to a V6 switched to Rx (receiver) mode. Pop a second V6 on your camera’s hotshoe in Tx (transmitter) mode, and you’re good to go. You have 4 different groups that you can assign flashes to and each group’s power can be controlled individually. When changing power levels, you can do it all conveniently from the V6-transmitter on your camera and you can do so for one group separately or for all groups proportionally. The V6 Mark II keeps all those cool features and adds what I have been hoping and waiting for ever since I switched to the Fuji X-system: High Speed Sync. Short of TTL, which I rarely use anyway, and High Speed Sync, which is about the only thing I miss from my DSLR days, the original V6 did everything I wanted it to. And now the Mark II adds just that one missing feature.

What is HSS?

Let’s backtrack a little. When you shoot flash, traditionally, you have to take the so-called X-sync speed of your camera into account: you can only sync a flash at shutter speeds up to the sync speed.

Now, did you notice the word ‘traditionally’? I put it in there because, for a couple of years already, most camera and flash manufacturers have found ways around this limitation, effectively letting you use your flash with sync speeds all the way up to 1/8000th of a second.

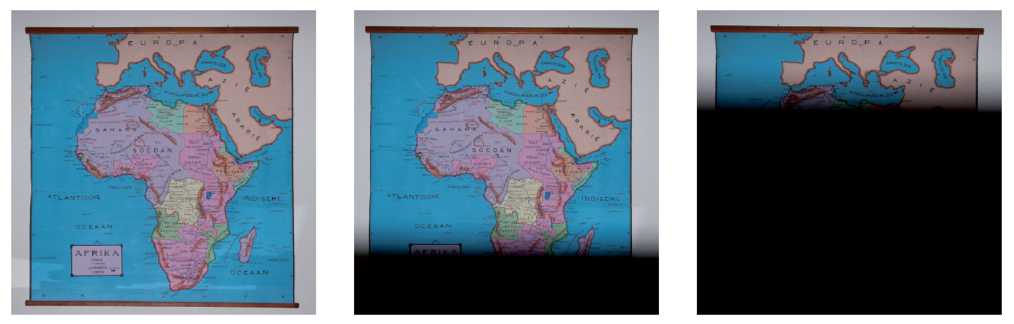

A flash used on a camera with a sync speed of 1/200th of a second. Left: 1/200th of a second, middle: 1/320th of a second. Right: 1/500th of a second. Failure to respect the X-sync speed of your camera will result in the infamous black bar across your image.

Why is this such a big deal for Fujifilm users?

As I said in the previous paragraph, most camera and flash manufacturers already support HSS, except… Fujifilm… They are working on an HSS enabled flash, that would even have the advantage of throwing TTL in the mix (Editor’s Note: on July 7th, 2016 Fujifilm announced their own EF-X500 flash featuring the high-speed sync). By contrast, the V6 Mark II is manual-only, although you can change that manual power level remotely. However, that flash still isn’t available. Latest rumors point at a September release. According to Fujifilm’s press release, the EF-X500 would sport an optical triggering system. The V6 Mark uses radio, which is more reliable in direct sunlight (which is exactly the kind of situation where you would need HSS). So, the upcoming EF-X500 and the Cactus V6 needn’t be competitors. On the contrary, they might end up working well together…

Working at 1/250th or 1/180th of a second with flash would have forced me to use very small apertures, resulting in a very busy background.

Now about those HSS advantages: there are two of them, and they’re both super important for flash users. No longer having a sync speed to worry about, means you can use those expensive fast Fujifilm primes wide open and still use flash, as the example below shows.

Thanks to HSS, I can use a wide open aperture AND flash. The background becomes nice and blurry, emphasizing the subject.

Thanks to the Cactus V6 Mark II, I was able to use flash (in this case a Cactus RF60, but I also tried it with a Nikon SB-900) and shoot at f/2.8 at 1/8.000th of a second. With any other trigger, I would have had to shoot at 1/250th of a second on my X-Pro 2 (and even 1/180th of a second on the older X-cameras). That means I would have to use an aperture of f/16. I don’t know about you, but I did not buy the 56 mm or the 50-140 mm to use it at f/16!

Now, in all honesty, there’s another way you could solve this problem, at least when your subject is stationary. That’s by putting a neutral density (ND) filter over your lens, in this example a 5 stop one. However, as anyone who’s ever used NDs will testify: using them adds another layer of complexity to your flash photography. Also, as they’re an extra piece of glass, the cheaper ones may have a slight impact on your image quality and the stronger ones will often introduce a colour cast, too.

Without High Speed Sync, the only way to use flash, e.g. as fill light when the light is really bright and contrasty outside, is to use a truckload of neutral density. In this image, I had to use over 10 stops to get the aperture down to F/1.8 to get the cinematic shallow depth of field that I wanted.

And finally, ND’s won’t help you if you want to freeze fast moving outdoor action, like dancers jumping, with flash outdoors. That’s because at those slow regular sync speeds, the ambient light that falls on your subject will cause some blur around it in the final image. For that blur to disappear, you need to use faster shutter speeds.

This image was shot with a Sony camera and a 600 Ws CononMk i6 EX Leopard using High Speed Sync. Up until now, you simply could not make this kind of action-freezing, flash-lit shot with a Fujifilm X-series camera other than the X100 series. Thanks to the Cactus V6 Mark II, now you can.

Normal HSS

This is where High Speed Sync comes in. I won’t copy the V6 user manual – in fact, it’s 100 pages long and you can download it here if you want to – but the procedure is rather straightforward. It took me 5 minutes to get my X-Pro 2, one cactus V6 Mark II trigger and one Cactus RF60 flash shooting in High Speed Sync. Honestly, I was surprised at how smooth it all went. Normally, the V6 will automatically detect your camera and flash system. However, you can manually set these parameters, too.

The Cactus V6 Mark II will not only enable HSS with Cactus’ own RF60 flash, but with just about any speedlight, like the Nikon SB-900 or the cheap Godox V850 flashes. The advantage of Cactus’ own RF60 is that it has a built-in receiver. In the case of non-Cactus flashes, you have to attach them to a Cactus V6 receiver. Although the trigger on your Fujifilm camera needs to be a V6 Mark II, Cactus are working on a firmware update that will support Power Sync if you use the V6 as a receiver with a non-Cactus flash (Cactus’ own RF60 has a built-in receiver, remember). For Normal HSS support with those non-Cactus flashes, you’ll need to use a V6 Mark II as a receiver.

The only thing you have to do – once – is ‘train’ your trigger to get to know your specific Fujifilm camera: for that, you need to go into the trigger’s menu and it will ask you to fire one shot at 1/1000th of a second. That’s all. Once that’s done, you simply set the trigger to ‘Normal HSS’ mode. Specifically for Fujifilm cameras, as they don’t officially support High Speed Sync yet, you also have to set ‘Forced HSS’ to ‘On’ when you want to shoot at speeds higher than your sync speed. Luckily, you don’t have to dive into any menus here: You simply push the rotary wheel on the back of the V6. When you’re back to using shutter speeds below the sync speed, don’t forget to push the rotary wheel again. I found myself sometimes inadvertently switching between those two modes simply because the wheel had bumped into something. Cactus have already replied they would fix this in the next firmware update.

Without getting too technical, what happens in Normal HSS mode is that the flash fires almost stroboscopically during the shutter speed of say 1/2000th of a second. Yes, it’s hard to believe but in that short period of time, the flash fires more than once but that’s what happens! The downside is that a lot of flash power gets wasted, but that’s the case for all HSS systems that work like this, also Nikon’s and Canon’s!

I put a flash outside, behind the door. Without the flash, either Serge would have been completely dark or the outside world would have been completely blown out. Thanks to HSS, I could use the 16 mm at f/1.4 and 1/8000th of a second. Without HSS, I would have had to shoot this at f/8 to stay within the X-Pro 2’s 1/250th of a second sync speed.

Power Sync

That’s why Cactus has also included a second way of letting you work beyond the sync speed of your camera, and that’s called Power Sync. This technology works differently: it uses a slice of the flash curve’s tail and matches that up with your shutter speed. So in a way, your flash acts as a continuous light source, if only for that very short shutter speed. For this technology to work, the flash duration needs to be as long (slow) as possible. That’s why it will only work at full power. The advantage is that less light is lost, so when there’s a lot of ambient light you need to tame, or you want to use very big, light-sucking modifiers, Power Sync might give you some more mileage. The downside compared to Normal HSS is that you cannot dial your flash power down from full power. In the V6’s menu, you can adjust which part of the flash curve is used, simply by turning a dial from 0 to 32. For example, for the RF60, I found a setting of 28 to be ideal. Back in the day, the Pocketwizard TT1 and TT5 system offered a similar option of adjusting the sync timing but you needed to program the units via your computer. Compared to this, Cactus’ implementation is incredibly simple and straightforward.

I’d recommend starting out in Normal HSS and using Power Sync when you really need to squeeze every last photon out of your flashes. Power Sync is also the option to choose when you want to work with studio flashes beyond the sync speed.

Two shots, both with the flash at full power. The darkest one (left) was shot in Normal HSS mode. The slightly brighter one (right) was shot in Power Sync mode. In both shots, the subject was standing at the same distance to the flash. So the difference you see is the extra power that Power Sync gives you over Normal HSS.

Power Sync is also the way to go if you want to use studio flashes. This shot was taken with the 600 Ws Godox AD600B, attached to a Cactus V6 Mark II receiver and triggered by a Cactus V6 Mark II transmitter on my Fujifilm camera. For the moment, when working with studio flashes, the trick is to set the receiver V6 in the Nikon flash profile.

So does this this mean you can sell your ND filters?

Not quite: if you really like to work with flash and use your precious primes wide open, there will still be instances where even at 1/8000th of a second, you’ll have too much ambient light at f/1.4 or f/1.2 and ISO 200. And your Fuji’s electronic shutter is not an option, as it does not work with flash at all. Although in a pinch you could drop your ISO to 100, I don’t recommend you do because it effectively decreases your dynamic range. In those cases, you might still want to use a two or three stop ND filter. Also, although HSS is certainly more user-friendly than using ND filters, it wastes flash power. So, an ND filter can still come in handy on those occasions where you really need to squeeze every last photon of light out of your flash.

Finally, if you want to work with bigger flashes that don’t play ball with Cactus’ Power Sync technology, you will still need ND filters to keep shutter speeds under your sync speed when working with wide open apertures.

Ergonomics and handling

The V6II is compatible in Normal HSS and Power Sync mode with Cactus’ own RF60 flash (obviously) but also with a lot of flashes that you might have lying around from your pre-Fujifilm days. For example, I tried it with an SB900 and it also worked. Oddly enough, the few flashes HSS does not work with, are the current Fujifilm flashes like the EF-42. For optimal compatibility and performance, you can choose the flash model (e.g. Nikon SB-900) in the menu of the V6.

Putting my old Nikon SB900 back to life – and not just ordinary life but life in the fast lane! By putting it on a V6 Mark II, I can use it in HSS mode with my X-Pro 2.

The Cactus V6 has an easy-to use interface with 4 direct-access buttons, a control wheel and a pass-through TTL hotshoe, but as a result of that, it’s also quite wide. In fact, on some cameras, especially the X-T10, it makes it hard to adjust the shutter speed dial. The easiest workaround is to set your shutter speed dial to the T-position and then adjust your shutter speed with the front dial anywhere between your fastest shutter speed and 30 seconds. You did know that trick, didn’t you?

On the X-Pro 2, there’s another thing to watch out for: don’t turn the lever that secures the trigger to the hotshoe too far to the right, or you will not be able to change your ISO anymore because it would refrain you from lifting the ISO dial.

Because of the design of the X-T1 and the newly announced X-T2, there is more clearance between the bottom of the trigger and the dials on the top of these cameras and I don’t expect any issues there.

Finally, make sure you slide the V6 all the way in the hotshoe. If necessary, push it a little. I’ve had a couple of instances where my flashes did not fire because I had not pushed it all the way in.

For this image, I exceptionally dropped the ISO to 100 so I could shoot at f/1.8 and still keep the background dark enough.

Conclusion

The V6 Mark II should be in the bag of every Fujifilm photographer who’s even halfway interested in using flash on location. It dramatically extends your creative options in terms of working wide open and/or freezing action and it does so in a way that is relatively easy to understand and set up, especially considering that Fujifilm does not have native HSS support at the moment. On top of that, it lets you put those old Canon or Nikon flashes that you might still lingering about in the cupboard to good use. Considering it’s currently the only trigger that currently does that, the price (under $200 for a pair) is a bargain, too. I know more than one Fujifilm photographer whose leather wrist wrap costs more than a V6!

For specifications and product details, visit the official Cactus V6 Mark II page.