I spent part of my childhood in a dark room my father set up in the bathroom of our small apartment in Bucharest. For years I helped him develop film and print photographs in that room. It was a magic place. This was during the Cold War era when in Eastern-Europe photography was a semi-legal activity, strangely not controlled by the secret police (the government forced people to register their typewriters, but not their cameras). I spent my days listening to Pink Floyd, dreaming, reading, drawing and painting. On my thirteenth birthday, my father let me use his bulky Rolleiflex Automat Model 2 and an East German Exakta Varex II. Developing photographs in the lab and roaming the streets of Bucharest with my cameras opened up a new universe for me, something magic, private, even sacred. I have been making pictures, dreaming, reading, drawing and painting ever since.

I have always shifted between “found” photography and conceptual photography, between factual representations and imagined realities. These days, when in Paris, Venice or Florence, I “find” images. At home, often listening to music, my sketchbook and a pen always on hand, I plot and later “make” images. The conceptual side of my work often has surrealist echoes and involves a lot more planning, people and props. Lately, I have been fascinated more and more by the juxtaposition of the real with the artificial.

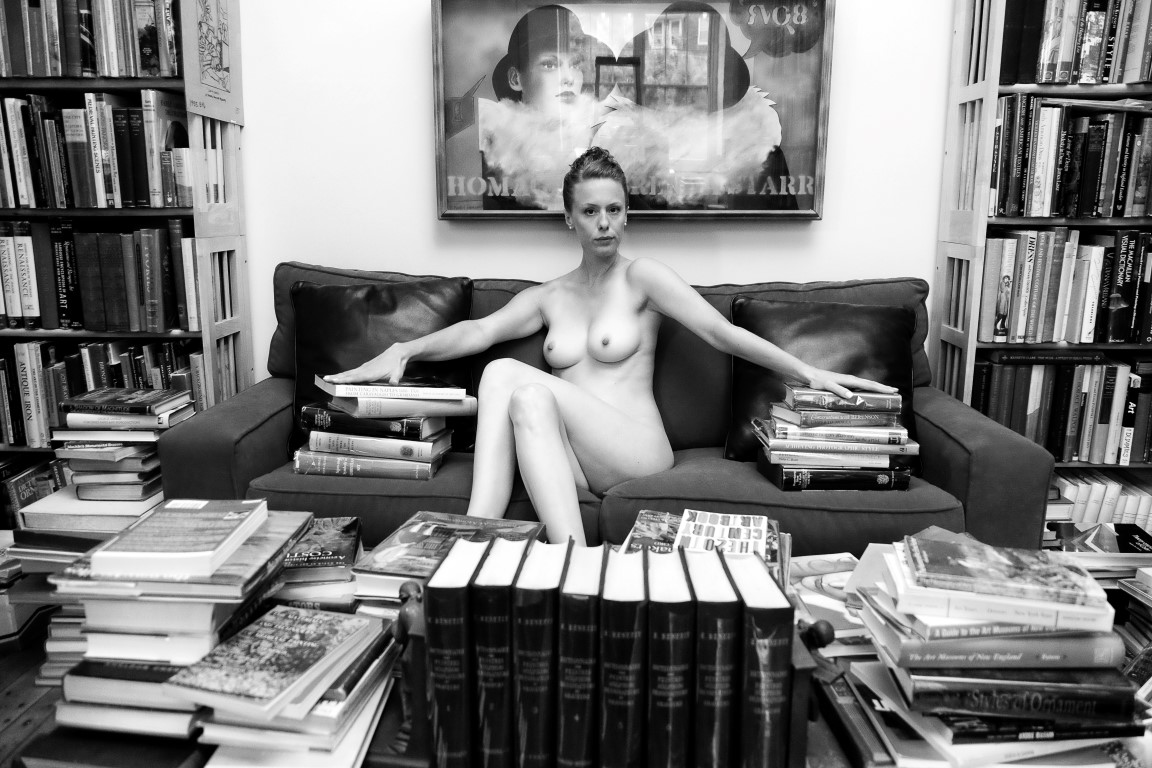

After moving to the United States, I have discovered a group of artists with whom I felt a sense of kinship: the work of Belgian painter Paul Delvaux, and Storm Thorgerson, the British graphic designer who created some of the iconic album sleeves for Led Zeppelin, Alan Parsons, and Peter Gabriel. Delvaux’s art features eerie nudes set in surreal settings. Thorgerson was a Salvador Dali with a postmodernist flare. (In 1975, for “Wish You Were Here,” he fashioned the famed handshake between two men, one of whom is on fire. In 1987, one year before Photoshop was created, Thorgerson managed to set 700 iron hospital beds on a beach in order to create the cover for “A Momentary Lapse of Reason.”)

The only reason I am bringing all this back is not because I am longing for the old, “better days” (in my case, almost always, nostalgia has manifested itself as a form of paralysis); it is not only because for me paying attention to the world around me through photography has become a state of mind, but because I look at my cameras as the ideal tools for extricating my dreams out of reality and reality out of my dreams while I become invisible. The Fuji X system has proven to be ideal for my recent artistic explorations.

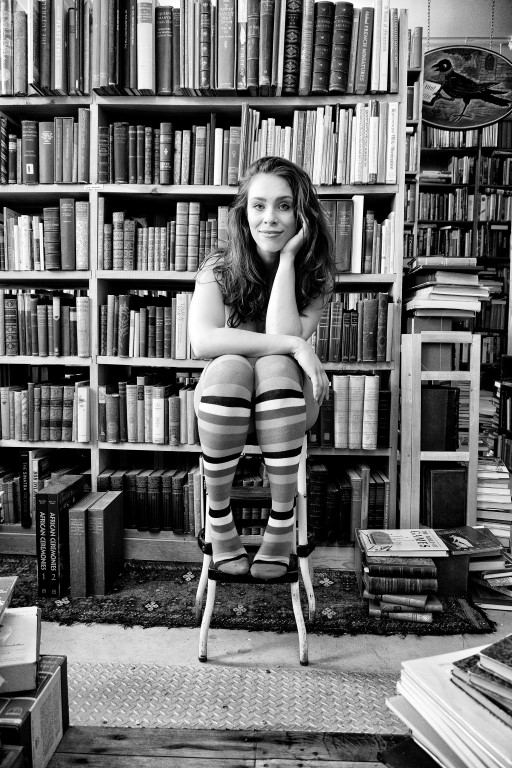

“The Bookstore Project” started with a visit to a bookstore and a dream. My friend G.J. Askins has built a labyrinth-like space in an old mill in Northern Massachusetts. Tens of thousands of books occupy every corner of a large, well-lit room. They rest on old wooden floors, tables, sofas and desks. During the day the room looks like an ancient city in ruins. At night, it resembles a strange forest or a set for a yet to be written opera.

In 2012, during one of my customary visits to the bookstore, I noticed a book of black and white nude photographs and a pair of wooden Santos hands resting on one of the tables. I placed the hands on the open book. The setting fit into my constant exploration of the juxtaposition of the real and the artificial.

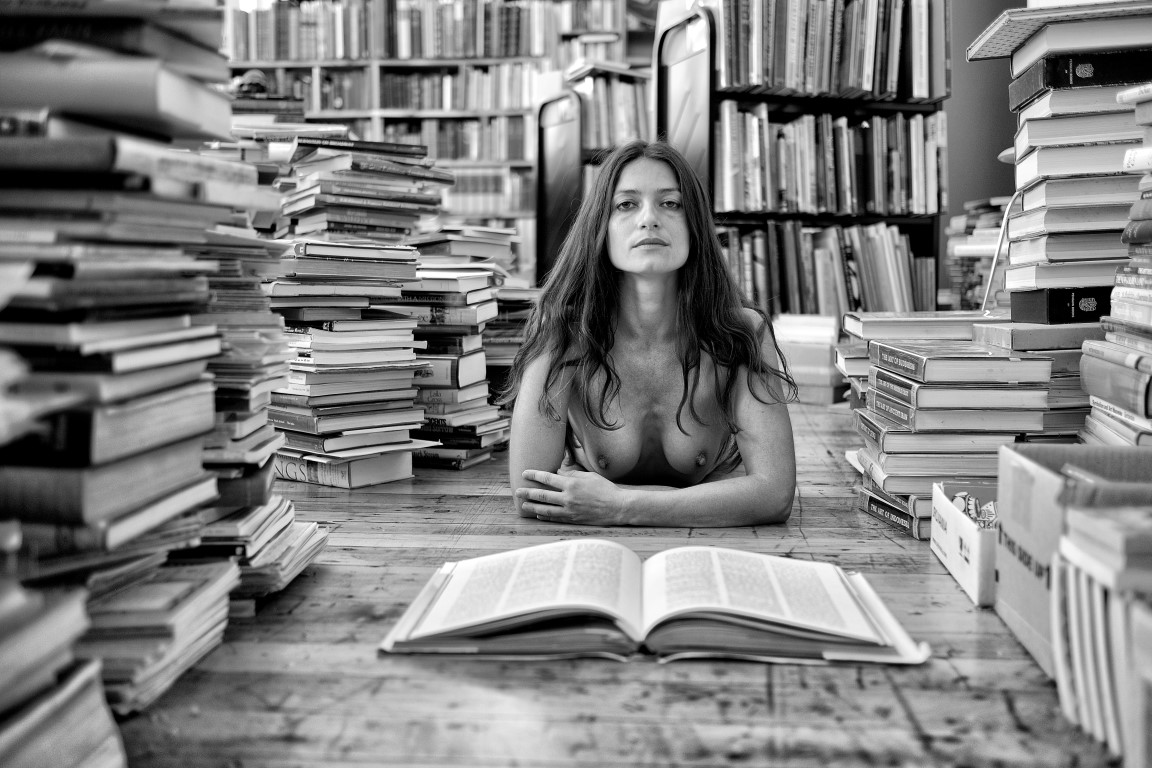

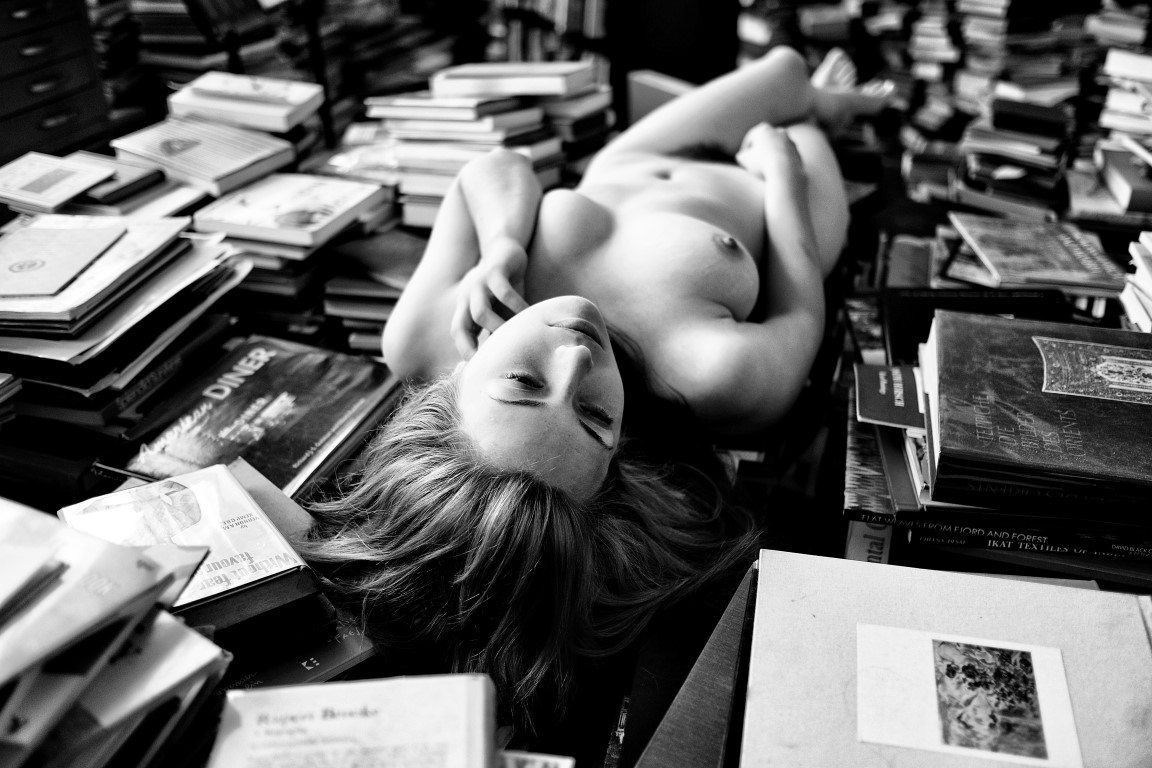

That evening, I had a dream. The Bookstore had no roof and was immersed in a dark blue light. It was raining. A nude woman was walking through the labyrinth of books, browsing through the soggy volumes, asking for directions to the Heathrow Airport. I woke up out of a Paul Delvaux painting.

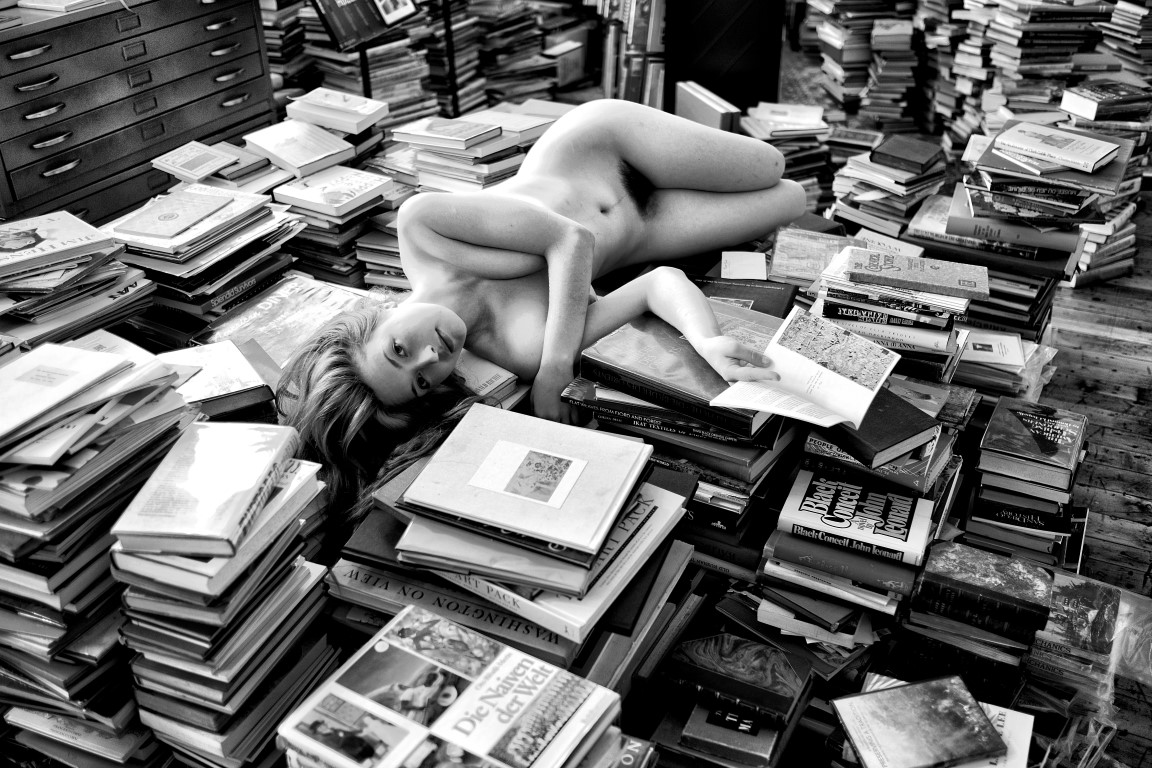

I called my friend, the bookstore owner, and asked him if I could do a photo shoot in his place. It would only take a few hours, I remember promising. It took me three years and close to 30,000 photographs to bring my dream to fruition.

For most of my life I used the Nikon system. When I started working on “The Bookstore” I used my bulky D7100, but after a friend introduced me to the Fuji x100s, I realized that I found my “invisible” camera system, the one that would allow me to stay out of the picture. By 2015, I owned a X-T1 and a X-Pro1. Most of the project was shot with these three cameras, using existing light and an occasional soft box.

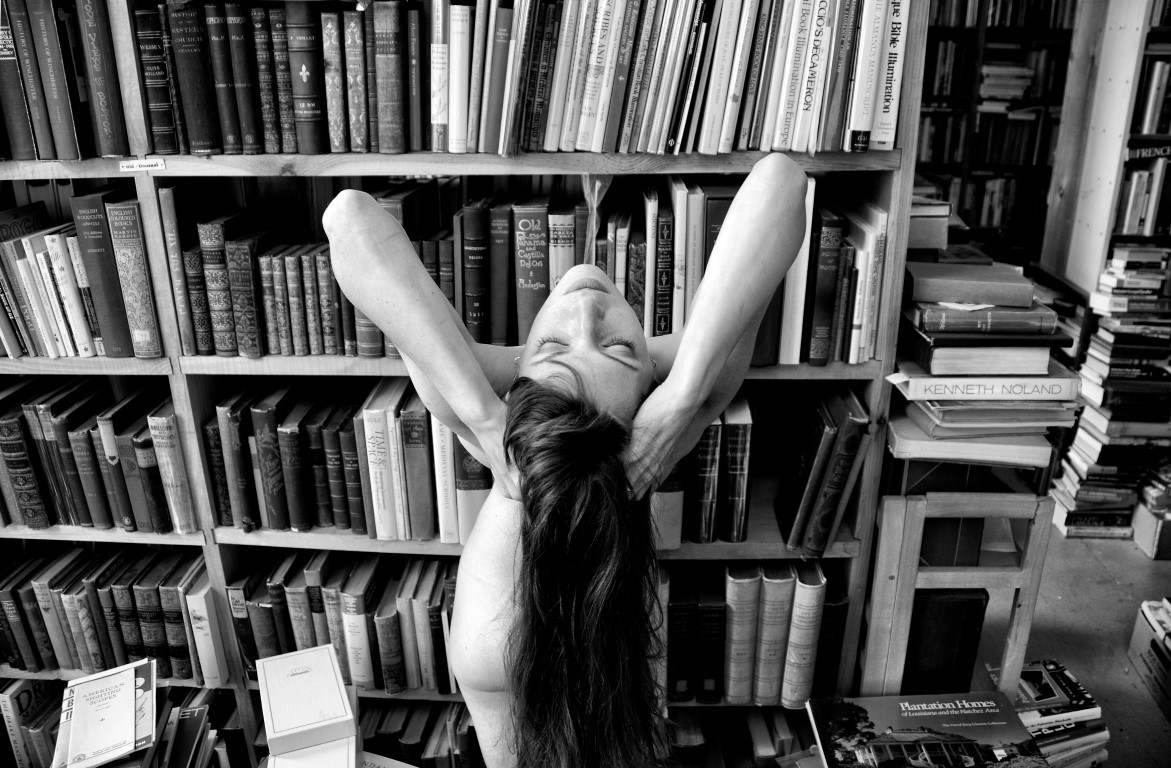

Working with nudes in a location like that requires a lot of planning and patience. Ideally, the photographer should remain invisible. I dislike the concept of “shooting” photographs and the inherent intrusiveness of the “lens in your face” type of photography. As an extension of the artist’s consciousness, the camera should never be a tool of aggression. (I am reminded of a wonderful video performance created by Alexander McQueen, where two robots are spray-painting a dress worn by the model Shalom Harlow that reminds me of that.) During the work sessions, I often instructed my models to try to behave as if no one was in the room, to ignore the “noise” around them. Often, they read to me while I was working: poems by Cavafi, and Neruda, fairy tales, and – in order to bring some comic relief to the scene – recipes from decades old cookbooks. I wanted to convey a sense of serenity and comfort within a setting. I am sure that Delvaux, Thorgerson and my days spent I my father’s improvised photo lab in Bucharest were all part of this.

Switching to Fuji cameras helped me achieve what I always wanted to do as a photographer: to allow my ideas to speak for themselves while I became invisible.

“The Bookstore Project” started in 2012. The physical space (an old mill in Massachusetts) has fascinated me for years. A strange, striking mess, it lacks the structure of a typical store where everything is usually carefully confined and catalogued. It is a bit melancholy – like an abandoned cathedral, an ancient city or an archaeological dig. I think of its owner as one of those ancient Irish monks who dedicated their lives to saving Western Civilization after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Maybe because of its location or maybe because in the age of the tablet and the selfie book readers are becoming a dying species, there are rarely any visitors in the store. More than anything else, the bookstore feels like a collection of silences. Yet, a repository of knowledge without any recipients craves to be repopulated like an old ghost town or a newly discovered planet waiting for a new beginning. The Garden of Eden, Alice in Wonderland, and the paintings of Belgian surrealist Paul Delvaux all came to mind. Hence the nudes.

My friend, poet Andrei Codrescu, believes that the series emphasizes the undeniable bond between eroticism and literature. On the other hand, I was more interested in the Poetic rather than the Erotic. I wanted to establish a sense of mystery, explore the connections between beauty and knowledge, and ultimately highlight the vulnerability of both Culture and Beauty.

Three years and 20,000 photographs later, I am finally putting the finishing touches on an exhibit and a book. Maybe I too, inadvertently turned into a monk trying to foolishly save Beauty and Knowledge. Yet, as I read this, I can’t help a smile: maybe it’s a lot simpler than that; maybe the whole thing is nothing more than an obsession, and in the end, perhaps even a small victory: Few could deny that books and women are one of the few sacred places left where beauty will continue to reside despite the constant convulsions of our troubled century.